I was Lead Product Designer in a cross-disciplinary team on a project spanning almost 3 years. The resulting product was successfully acquired by a global AI technology firm.

I was initially approached by an Academic Surgeon at Imperial College London to become part of a project looking to use digital technology to improve Clinical Handover between hospital shifts, typically at 8am and 8pm each day.

The goal was to measurably improve the effectiveness of Clinical Handover, thereby reducing potential harm to patients.

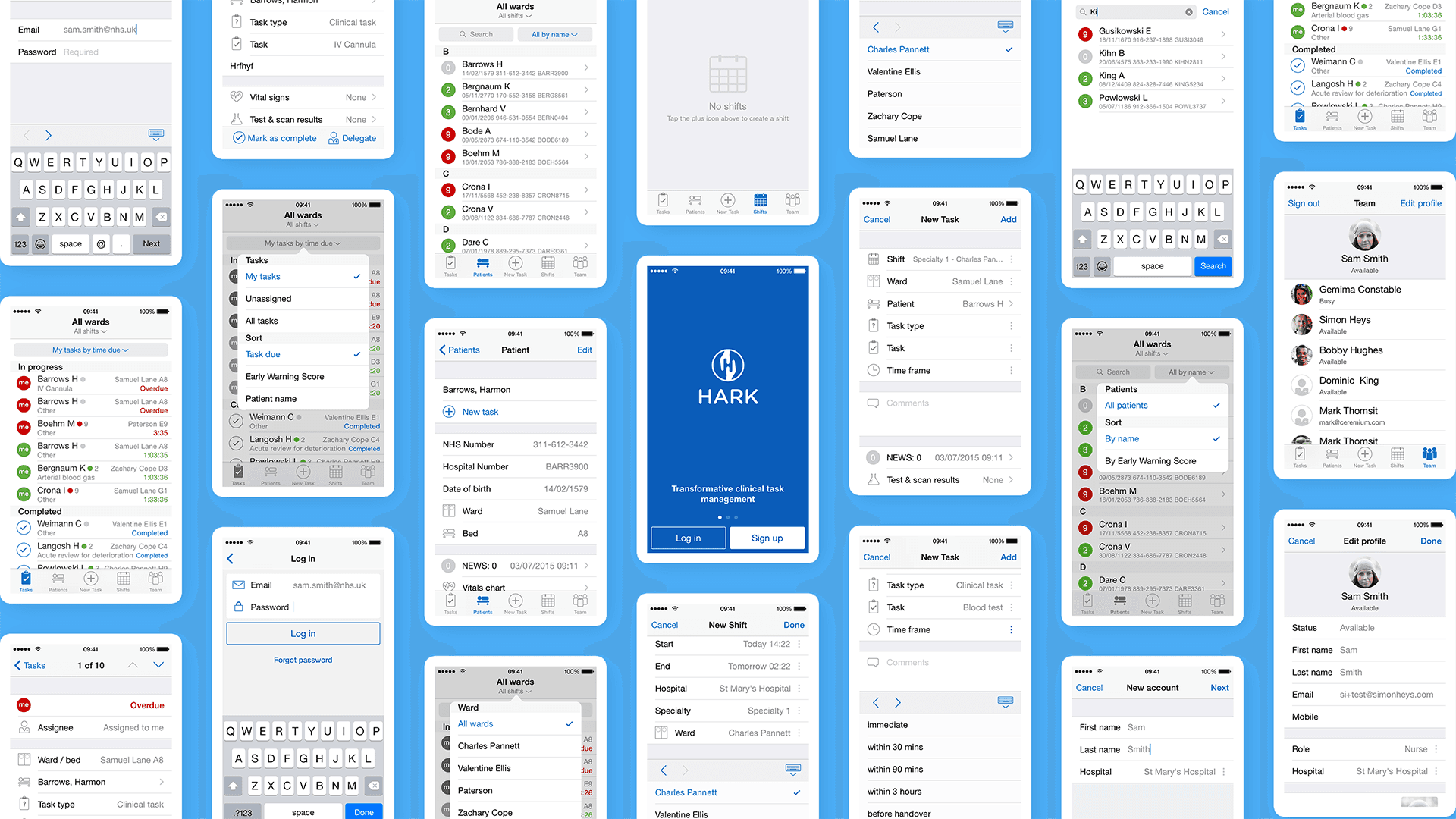

Note that all screenshots contain only fake data and all photos are heavily obfuscated where necessary.

Information about patients on a ward is printed and then kept up to date with hand-written notes over the course of a shift. This can result in incomplete information handover and a loss of accountability. Examples of these confidential records are often found littered accidentally on the ground of the hospital car park.

The existing system for managing and delegating tasks was via pagers (‘bleeps’) and landline phones. Receiving a bleep and then following up only later by landline is incredibly inefficient and leads to tasks not being actioned in a timely manner. There is no way to prioritise or delegate tasks and this could potentially lead to a dangerous situation.

The practical challenge at the outset was to start from zero and deliver a testable MVP iPhone app within 6 months. Success in addressing the above would potentially unlock further funding to continue and extend the project further.

Teaming up with two other UX Designers we arranged six direct research sessions. These typically included 30 minutes before and after Clinical Handover, either in the morning or evening and under the guidance of multiple doctors. One of the most memorable sessions was shadowing an A&E doctor, walking what felt like miles of corridors and tackling an unending stream of cases.

The direct research sessions were only the beginning of our multi-year journey to fully understand the complex ecosystem of interactions between our potential users and their typical day-to-day work and environment.

The outputs of the research were captured as a series of current and target process maps, capturing typical problems faced by our users and indicating where intervention by an App could be a potential solution. We identified the opportunity to extend the scope of the app, adding task management and integrating it into the current vision of Clinical Handover.

The team refined the target state into a set of core features for MVP that could be feasibly built and tested within our time window.

I worked with a back-end engineer and built the initial MVP as a native Objective-C / Cocoa app for iOS. Being fully native allowed us to make proper use of push notifications and create optimised user inputs where we would need to interact with the iOS keyboard.

Throughout the development of the product we strove to create the best user experience, making the app as fluid and responsive as we could. This meant sometimes taking an extra step to push beyond what was available by default in our front and backend libraries.

The back-end engineer used server-side events (SSE) where we needed parts of the app to update in realtime such as the list of tasks. SSE is not supported natively in Cocoa so I wrote an Objective-C implementation of Server-Sent Events which complies to the official specification and validates against the test suite in WebKit.

Our users make use of an National Early Warning Score (NEWS) which is a single number derived from the vital signs of a patient. We worked with a clinical member of the team to determine a test suite of vital signs and expected NEWS which we used to create a provably correct algorithm in the app. The NEWS score is updated in realtime, giving the user immediate feedback as the vital signs are entered.

The app has three key forms for creating a task, adding patient details and creating vital signs. These were kept as compact as possible to minimise scrolling. I spent time refining the user interaction, making sure it was easy to tap 'Next' on the keyboard in each field to actually move to the next, without the cognitive overload caused by the keyboard popping in and out of view.

This was a subtle challenge and eventually required creating a few custom keyboard inputs, including a custom and more legible 2D ‘Select’ input which was found to be a great improvement over the default 3D ‘spinner’. The resulting forms can be read and filled in as quickly and efficiently as we thought possible.

The initial MVP was a huge success. The Academic Surgeon and their team and undertook a series of simulation tests which proved significant gains in accuracy and time savings over pen, paper and bleeps.

As a result the team was successful in securing further funding and continued to improve and test features in a series of isolated sprints.

We eventually reached far enough along our roadmap to have a universal iPhone and iPad client with realtime communication working against a secure container-based backend system.

I created a simple identity for the app, an icon using hands to signify handover and teamwork and forming the letter H for Hark. The app makes use of red-amber-green for status which made blue the natural choice as a primary colour.

The app interface is deliberately faithful to the native look of iOS, using native navigation and controls where possible. This makes the app instantly familiar to users and makes them confident that they already know how to use it.

We created examples of several different real-time dashboards to show the potential power from aggregating data to give actionable insight across a ward or whole hospital.

Pilot studies showed that Hark improved information transfer within clinical teams in 22 out of 24 key areas with response times 37% quicker than a pager.

What started out as a relatively small project eventually scaled into a multi-year multi-platform product. The product was received with genuine interest and enthusiasm wherever it was shown.

This was a result of embedding user research and testing into the product, and having a brilliant Academic Surgeon and Product Owner on the team with a deep understanding and first-hand experience of the pain points we were solving.

Alongside product development we invested significant time putting material and infrastructure in place to run a pilot study of the platform at St Mary’s Hospital in Paddington. However due to unexpected events (see Outcome below) we never had the satisfaction of seeing the pilot through.

The product was successfully acquired by Google DeepMind.